Across 21 months and two Space Hulk games, Full Control have done their best to teach players the concept of Overwatch. It’s the most crucial command available to adherents of the Codex Astartes; the end-of-turn action that enables your team of Terminators to prepare for what’s coming around the corner.

But despite their efforts, they couldn’t brace players for the impact of a tight budget. Unmanaged expectations eventually did for the Danish studio who dared to try and build their dream tactics game.

“I don’t regret anything,” said Thomas Hentschel Lund, Full Control’s CEO and final remaining employee.

It began, as so many dreams in the games industry do, at GDC.

“Was that four years ago? I can’t remember,” mused Lund. “So many parties since.”

Whenever it was, it was a cold morning – and Lund was standing at an open fireplace in a San Francisco hotel lobby. In time, he was joined by another man – another industry professional. Lund told the man about the mobile games he’d been making with a handful of full-time staff in Copenhagen – games with grids, percentage-to-hit calculations and flamethrowers. He told the man that what he’d really love to make was a Space Hulk adaptation.

Only when the man handed Lund a business card did the Danish developer recognise Ian Livingstone, life president of Eidos and onetime co-founder of Games Workshop.

“That was totally a luck thing,” recalled Lund. “Right place, right time, pitching to a guy you don’t recognise.”

It was luck, too, that Games Workshop were going through their most cataclysmic licensing change in many years. THQ were falling apart, and their grip on the Warhammer 40,000 license was loosening. After a decade enlivened only by the Dawn of War series, Games Workshop were suddenly dividing up the most curious corners of their universe between indie outfits: Necromunda; Battlefleet Gothic; Mordheim.

“I think Games Workshop had a wish to actually get more games out into the hands of fans,” said Lund. “Because that universe is just so big.”

They were keen, too, to push into the mobile and tablet markets. And there, right at the beginning, was Thomas Lund with a pitch for Space Hulk. He told them he wanted to make a straight-up adaptation of the board game, not only for iPad, but for PC – the platform he’d been pushing Full Control towards for years. And several months, emails and pitches later, Lund found himself clutching the license he’d always wanted.

Morale was good. XCOM had introduced turn-based tactics to a new, larger generation. But money was tight – and the Space Hulk team would total just 15 people at its peak.

Rather than conceive an untested design that might exceed the bounds of their short production cycle, Full Control decided to pledge their service to the original board game – transposing Space Hulk as faithfully as they could to a new medium, retaining its rules wherever possible.

Meanwhile, they’d acquired the license for a new Jagged Alliance game from bitComposer, and taken to Kickstarter to raise funds. Lund’s hope was that he could set his team to work on another sacred name in turn-based tactics – just as they were wrapping up on Space Hulk. But he also felt as if the studio was running on potential and promises.

“Obviously, we could see where this could go, given the right framework and budgets,” said Lund. “Explaining it to be people, especially in the Jagged Alliance community that had been burned before, was really tough.”

Space Hulk was published on Steam in August 2013. It captured exactly the claustrophobic corridor combat of the board game. But it couldn’t match Firaxis for technical polish, suffering from shonky animations. And it was slavish to a fault: hand-to-claw encounters in particular felt tense when decided by dice on the tabletop, but looked clumsy and unfair in their new digital shell.

“We made the game that we promised to make, and we actually made a large group of hardcore board game fans very, very happy,” said Lund. “At the same time, we also made a large group of video game fans angry.

“Looking back, I still think we did it right. Any other approach would have killed us. Something bigger was simply not possible with the people and the money I could dig up.”

Space Hulk sold well – almost too well. Games Workshop set the team Lund had intended for Jagged Alliance: Flashback to work on a long run of DLC. But Flashback couldn’t wait; the company had an obligation to its backers. And so a handful of core team members were moved over to Jagged Alliance, and new hands were hired on to fill the rest of the roles.

Full Control, just fix or six people strong before Space Hulk, had grown to 25.

“That was never the plan,” said Lund, a little sadly. “The burn rates associated with that number of people are comparatively staggering. Suddenly you are running a business, instead of being part of the game production.

“That might have been the one mistake – that we ran the Kickstarter at the time that we did.”

The Space Hulk team, however, had momentum. They had an engine, and the whole-hearted backing of Games Workshop – who asked what they wanted to do next.

The answer was clear: they would revisit the ideas suppressed while translating the board game. Space Hulk: Ascension would be a semi-sequel, built with an entirely different ethos. For the first time with Space Hulk, Full Control weren’t simply interpreting – they were designing. It felt like being set free.

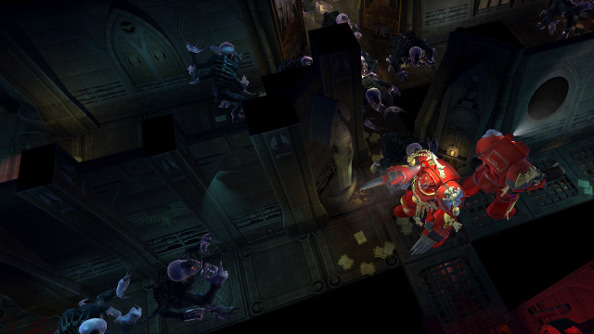

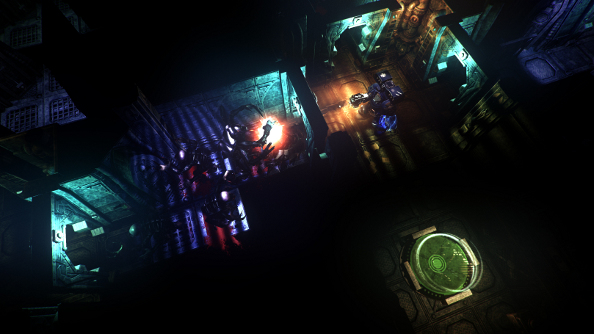

From the off, they knew they wanted to deliver on the premise of entering unknown space. By its nature, the board game provided the Terminators with full visibility – ‘blip’ tokens could conceal the nature of enemies, but not their positions. By contrast, Ascension hid its genestealers behind what might be the thickest fog of war ever committed to code. The first-person camera, a nice atmospheric touch and hangover from the first game’s UI, came into its own as players were forced to squint into the dark.

Terminators were personalised for the first time, via levelling and equipment upgrades that persisted between levels. An XCOM-style permadeath system could see downed marines replaced with rookies, if players wanted. Space Hulk had always been about sacrifice; knowing when to cut a soldier loose and escape with the rest. Now, the threat of permanence made those equations far less utilitarian and far more difficult.

Gleaned from XCOM, too, was a more granular sort of maths reliant on percentages rather than D6.

“Changing the entire ruleset made a good difference,” said Lund. “But that’s also the scary part, where we were on shaky ground. In the first one we could stick to the proven rules that had been iterated on for ages.”

It worked, and a public with low expectations started to catch on. Sales of Ascension were strong, but slower than those of its predecessor. While Space Hulk had ridden a hype wave, Ascension was forced to rely on word-of-mouth.

“People play it and think, ‘Yes, this is actually the game I wanted the original to be’,” said Lund. “That just takes time to spread out.”

Unfortunately, Full Control didn’t have time. Flashback had just barely scraped its Kickstarter target – allowing the studio to make a game at approximately half the scope they’d hoped for. In pre-release interviews, Lund told press that his team couldn’t possibly match Jagged Alliance 2 for scale, and would provide comprehensive modding tools so that fans might build what they couldn’t. But Steam user reviews were unforgiving in the extreme (“We got slammed,” said Lund. “It hurt a lot.”).

Sales were “horrible”: “That was one of the nails in the coffin, really.”

What made acceptance all the more galling were the projects that had nearly been. Over the last year, Lund had begun pitching ideas to publishers.

One was a Western in the style of Jagged Alliance, with a persistent posse and an open world in which you’d evade a sheriff with an ever-growing pool of deputies. But a cruel quirk of fate saw three or four other similar games pitched during last year’s Gamescom. The potential competition made publishers nervous – and Hard West was the only one to make it, thanks to Kickstarter.

Another was a real-time WWII prison escape pitch – “Think Commandos, but in reverse” – which would ask players to scour kitchens for utensils to distract guards with view cones. That went “very far along” with one publisher before it was dropped.

Full Control had plenty of goodwill left at Games Workshop, too, who after Ascension had floated the idea of another Warhammer 40,000 game. Lund says the mystery project would have occupied an even larger team for a few years of production.

“But for a lot of reasons it just didn’t happen,” he said. “Nothing to do with the game idea, but it’s a hard sell going out to publishers these days and asking for larger budgets. Even if you go in with a big, big license in the bag.”

Games Workshop were still signing off on Ascension DLC – but it wasn’t enough.

Lund had a choice: keep on running until the money ran out, like so many games companies have done before, in the vain hope that another project would emerge. Or he could do what he did: see to it that nearly everybody on that team of 25 landed new jobs, and that Full Control’s journey ended not in bankruptcy but in just that: total control.

“[It was about] being able to touch down with a few bruises,” said Lund, “but making sure that everyone gets away with a good experience instead of running our head into the wall.”

The company still exists. The technology is still there. Lund has the option of porting Ascension to new platforms via third-parties in the future. But the dream is on hold.

“It’s a mixed feeling,” said Lund, reflecting on Full Control’s final, very public period. “I think it’s good for a lot of people to see some of the struggles that everybody has in this mid-size. All of us are struggling to make the best possible game on almost no money.

“We’re fighting for the same publishing space. And we’re struggling to create quality games that can compete with AAA titles in our own small niches and genres. We’re trying to do our best that we absolutely can, communicating everything that we can.”