This is the third instalment in a series looking at pivotal games in the history of PC gaming. Whether due to their scope, amibition, sheer quality or otherwise, these are some of the titles that have defined the medium.

Robert B. Marks is the author of Diablo: Demonsbane, The EverQuest Companion, and Garwulf’s Corner. His newest book, An Odyssey into Video Games and Pop Culture, is coming out on October 15th, and is available for pre-order in print.

Full disclosure: Blizzard’s Diablo, released in 1996, is a game that has been very good to me.

My first published book was Diablo: Demonsbane, an e-book that launched the entire Blizzard fiction line. My 2000-2002 column, Garwulf’s Corner, ran on Diabloii.net, and used Diablo and Diablo II as a jump-off point for almost every topic. So Diablo and Diablo II have a very special place in my heart, and I am admittedly somewhat biased towards them.

They are also two of the most influential multiplayer games ever made.

It’s easy to take internet multiplayer for granted today. But in 1996, the internet was uncharted territory. Most multiplayer play took place over local area networks and modems, and whether the internet could be a successful venue for multiplayer games was an open question. A lot of companies thought it could, and were willing make huge gambles on it – both Origin and Verant were working on massively multiplayer games (Ultima Online, released in 1997, and EverQuest, released in 1999, respectively) that would launch over the internet, as opposed to directing players to connect to their own servers via modem.

This didn’t mean that internet multiplayer play was absent, but it had severe challenges. Arguably the first attempt to make internet multiplayer gaming work was id Software’s Quake (released in mid-1996), but finding an online Quake server could be difficult at best, requiring players to locate individual IP addresses that were published or shared on websites. Three programmers, Joe Powell, Tim Cook, and Jack Matthews, created QSpy, a utility for locating game servers that would later become the GameSpy network. While this early attempt was a success (GameSpy would become a standard tool for online multiplayer matchmaking until it was shut down in 2014), in 1996 it was too limited to serve as a proof of concept for gaming over the internet as a whole.

What was needed was a smash success, something that demonstrated that the internet was the right tool for multiplayer gaming beyond any shadow of a doubt.

And thus came Diablo.

Like most of its contemporaries, Diablo came with a multiplayer mode, allowing players to connect to each other’s computers through modems or a network. But, it also came with a third option: Battle.net, a matchmaking service built directly into the game. Players would log on to the Battle.net servers, which would connect those hosting multiplayer games with those who were looking to play in them. The service was a runaway success, with Diablo selling 2.5 million copies, and hordes of gamers descending on Battle.net to join forces and take on the dungeon.

It also helped that Diablo was a very good, deep, and even revolutionary, game.

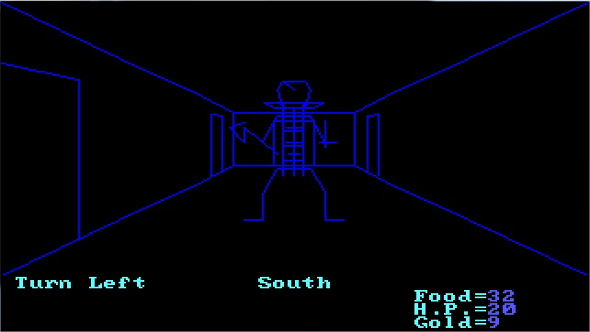

Like so many videogames, Diablo was born into a genre that already had at least a decade of history behind it. It was far from the first game to procedurally generate its levels – in 1978, Don Worth released Beneath Apple Manor for the Apple computer, and Richard Garriott’s Akalabeth: World of Doom was first released in 1979, with a general release in 1980. 1980 also saw the release of Rogue, a procedurally generated dungeon RPG by Michael Toy and Glenn Wichmann that lent its name to its sub-genre: roguelikes.

It was also far from the first action-RPG – Bokosuka Wars, released in 1983, was developed by Koji Sumii and featured real-time combat and characters levelling up as they gained experience. Action-RPG games became a staple of Japanese videogame design, with Nihon Falcom Corporation’s 1984 title Dragon Slayer considered the founder of what we would now recognize as a modern ARPG. Unlike many other videogame genres, action-RPGs grew to their maturity more on consoles and in arcades than the computer, with titles such as The Legend of Zelda (published for the Nintendo Entertainment System in 1986) and Atari’s Gauntlet (appearing in arcades and on the NES in 1985) epitomizing the genre.

What made Diablo revolutionary was its interface. Most games had been progressing towards more complex interfaces, with different button presses or mouse clicks required depending on the action to be taken. Diablo, on the other hand, streamlined its interface to the point of base simplicity – a keyboard was only required for typing in the name of the player character. The entire game could be played and won with a two-button mouse – and with opportunities to use the second button few and far between at that.

What Blizzard understood was that every additional step a player has to take to perform an action inside the game takes the player further away from immersion. With Diablo, whenever the mouse highlighted an item, monster, or NPC, a single click performed the appropriate action, from picking it up to slashing with a weapon to starting a conversation. This helped keep the player immersed in moving the game forward, giving Diablo some of the most immediate-feeling action since id Software’s Doom.

It also had an often unrecognized level of depth, which the game trusted players to take or leave as they saw fit. Scattered throughout the dungeon were various tomes, telling the backstory to the game and the world. If there was an overriding theme, it was corruption, carried through the backstory, to the dialogue of the NPCs, to the fate of the player character. If anything, the story dramatized the famous quote by Nietzsche: “He who fights with monsters should be careful lest he thereby become a monster. And if you gaze long into an abyss, the abyss will also gaze into you.” Diablo is not a game with a happy ending – having fought his or her way through the dungeon, the player character is so corrupted by the end that rather than destroying the soulstone through which Diablo has taken over the young prince’s body, they drive it into their forehead. Instead of being defeated, the game ends with Diablo freed from the dungeon and in an even stronger body than before.

Diablo was an undisputed success, but it would be its sequel, Diablo II (2000), that perfected what Diablo had created. Where Diablo was a confined dungeon crawl, Diablo II expanded the world and the mythology with an overland campaign. Diablo’s multiplayer was a stripped down version of the single-player game, with numerous quests removed. Bizarrely, this had made the multiplayer game more winnable – in single-player mode, it was all too easy for an unlucky player to find themselves stuck, with most of the dungeon emptied and no way to get enough additional experience or gold to get past a difficult section. In Diablo II, both the single-player and multiplayer games were identical, with areas regenerating their monsters every time the game was loaded up – this meant that multiplayer games were not missing quests, and single-player games allowed players to grind it out until they could progress through a difficult section. Diablo II also expanded on the character class advancement. Where Diablo had a magic system driven by the characters reading books to gain spells, with most character differentiation taking place in the base stats, Diablo II gave each of its five heroes a unique skill tree, making the experience of playing each class different and distinct.

If Diablo was thematically about corruption, Diablo II was about salvation. Unlike the hero who descended into the dungeon in Diablo, the heroes of Diablo II are not corrupted by the experience of fighting monsters. They travel through and save entire regions, protecting innocent people from the threat created as Diablo wanders across the landscape. And, once they strike Diablo down, they destroy his soulstone. Where Diablo ended in defeat, Diablo II ends in a well-earned victory. The abyss may have stared back, but to no avail.

Diablo II was an even greater success than Diablo, selling over 17 million copies and remaining on videogame bestseller lists for years after its release. Between the two games, they revitalized part of the RPG genre, and even spawned a number of imitators like Ascaron’s Sacred (2004), all vying to become a “Diablo-killer.”

Despite all of this, Diablo was perhaps most influential in the world of online gaming, where it proved, beyond any doubt, that the internet was the future of multiplayer. It opened the door for companies to build online play into their games with confidence, and if we are able to take online gaming for granted today, it is in large part because Diablo showed us just how successfully it could be done.