Harvey Smith, co-creative director on the Dishonored series, has a videogame career that spans two decades. It started with a love of systems-driven experiences – games with meaningful interactions, where worlds feel alive, important NPCs can die, and where you can usually hide in some kind of bin. This genre, loosely defined as the ‘immersive sim’, has much more to it than immersing yourself inside waste receptacles, however – it’s about creating the feeling that anything can happen, the knowledge that one interaction can snowball into something else.

If you love the classics, check out our list of the best old PC games.

For example, if you shoot a guard in the head with a crossbow bolt in Dishonored 2, it’s silent. But if he’s stood near a window, the force might smash his head through it, alerting nearby sentries. When it all unexpectedly kicks off, you have to adapt. It’s these interactions that make the genre special, working in tandem with their cohesive, story-filled worlds. This is what drew Smith to the genre.

His journey began at Looking Glass Studios where he worked on System Shock as lead tester for ten months. “The reason I got that job was, I came into the company and was the world’s biggest Ultima Underworld fan,” Smith remembers. “When I heard that System Shock came in to test, it looked interesting, but then I heard it was by the people who made Ultima Underworld and I went to my boss, Kay Gilmore, and I said to her ‘who do I have to kill to get a role on this project?’”

Looking Glass Studios’ Doug Church is one of Smith’s heroes of game design. When they met, Church had already attended MIT, he’d worked on a tank simulator at DARPA, and here he was at this exciting studio, working on games with a singular vision: System Shock, Thief, Ultima, Terra Nova, and more – they all took aim at one goal. “It’s about making an environment that feels – even if it’s not ‘realistic’ – complete and plausible,” Smith explains. “It gives you the design space, the interactivity space to actually explore. A lot of games, they either don’t have the fidelity – like, you look around and it’s a room, you move on, that’s it – but there’s environmental storytelling, and there’s also the time; it’s player-paced.

“There’s also poking and prodding and opening cabinets. I mean, if you’re in a hovel and there’s a sad implication that a poor woman lives there but, amongst all this garbage and clutter in the trashiest part of town, she has this beautiful pearl fan on her dressing table – it re-contextualises everything about her. This is maybe the one nice thing she has in her life, and when you steal it, maybe you feel something. Maybe you don’t. I remember people saying none of that matters: ‘I just grabbed it because it was worth five gold’. I think they’re wrong. I think we’ve proven over time that people definitely have an emotional, contextual reaction to what they’re doing in games, and you can either cater to that or not cater to that. That’s what we try to do: we try to facilitate that.”

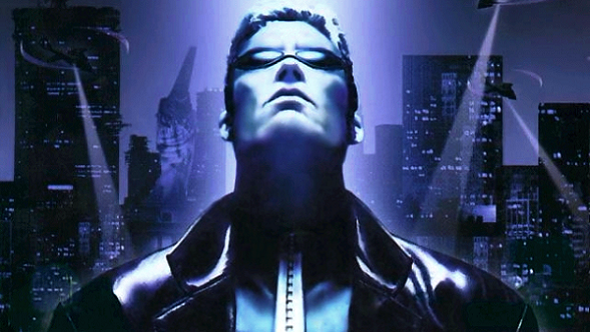

Smith famously did exactly that when he and his team developed Deus Ex and its sequel, Invisible War. Deus Ex certainly wasn’t the first game of its type, but it popularised the genre to a certain extent – though it was still niche – and it set the template for similar games to come. “I remember when we made Deus Ex and I was sitting in Warren Spector’s office and I think Doug Church was talking to the art team or something,” Smith recalls, “and Doug was trying to tell me – because I was like ‘oh my god, we could have done this better or that better’ – ‘you guys are going to be wildly successful,’ he said. And I was like, ‘what are you talking about?’. He was like, ‘everybody’s talking about the game already’. He had so much more experience than me at the time and he could see the writing on the wall – we had just done this thing that immersive sims had been trying to do for a long time, which is make one that everybody noticed.”

The original Deus Ex constantly pops up in ‘best PC games’ lists, and for good reason. It’s a classic. Even in 2017, Deus Ex does things a lot of modern games don’t even attempt. Because of its reception, both critically and commercially, you’d have been forgiven if you expected an explosion of this type of game to follow. However, it never happened. “System Shock, Thief, or Underworld – those are great fucking games,” Smith exclaims. “It’s just that, in many cases, they just didn’t sell very well. Deus Ex was the first one that got a lot of attention and a lot of lasting power. It didn’t sell anywhere near as well as BioShock or Dishonored, but it was certainly a move in that direction. Then, years and years later, BioShock was an even bigger version of that. Then, years and years later, Dishonored was a big version of that.”

These days, however, people are worried that the genre’s future is in trouble; that the audience is moving away from thoughtful triple-A experiences. Deus Ex: Mankind Divided’s sales numbers saw the marquee immersive sim series put on hold, despite the ending suggesting that more games were planned. Publishers Square Enix also dropped Hitman, a third-person game that shares DNA with the genre, placing you in living sandboxes where NPCs go about their business regardless of player input. Elsewhere, Mass Effect: Andromeda’s reception saw the sci-fi RPG series suspended, while developers BioWare – famed for creating branching, interactive stories – are now developing Anthem, a shared-world multiplayer shooter, as well as helping to make Star Wars action games.

While Andromeda doesn’t sit in the same genre as Deus Ex, Dishonored, and Arkane’s Prey, its fate is evidence that audiences are gravitating towards multiplayer games with an action focus. Even Rockstar didn’t bother creating any single-player DLC for GTA V, instead putting their resources into constantly expanding GTA Online, because that’s where the money is. Of course, the immersive sim is evolving, too. Dishonored is just as fun if you play it like a vengeful ghost, tearing through levels with your supernatural abilities, only occasionally eavesdropping from a bin. It’s an action game with brains, if you want it to be. Times are changing, but the genre can and will change with it. At least, that’s what Smith believes.

“I think we’ll continue to adapt to the audience, because what people want drives the budgets,” Smith explains. “Audience taste and the market drives a lot of the feature-set and people have to adapt. That said, I think there are ways to bring the values of the immersive sim into the new world. So it will always exist, in my opinion, with the values being absorbed by different games.”

You can already see this happening now. The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild arguably pushed the open-world genre forward, and it did so by adopting the ethos of the immersive sim. You have limited tools that constantly need to be replenished, forcing you to come up with creative solutions to battles. Maybe you’ll roll a boulder down a hill, perhaps you’ll start a forest fire, or you might sneak past the enemies in your way. You can even use your powers in creative ways the designers didn’t intend, cobbling together makeshift vehicles with Magnesis, a telekinetic lift, or solving puzzles with unconventional methods. Outside of triple-A games adopting these values, we’ll also begin to see immersive sims created in the indie space. Games like Consortium: The Tower prove that there’s an audience, raising funding through Fig to create a first-person RPG set in a single city block. Elsewhere, we might even start to see completely different types of games spawning from the genre.

“You’ll notice that the production values in indie games are going up, so we’re right around the corner from maybe like a Cambrian explosion of the ‘walking simulator’ getting to the next level where it’s like one step more dynamic, in a sense that things are happening in the world,” Smith tells us. “Tacoma is a good pointer in that direction. You’ll have adapting triple-A games that bring the values forward into some new form, you’ll have people that are true to the original form, and you’ll also have indie games that are like ‘well we can’t do everything, but we can take most of this base and take two or three features and go forward with that’.

“I wish everybody was working on this kind of game, because I’d just love to see the immersive sim that’s not based around combat – perhaps based around surveillance. The immersive sim that’s not set in a fantasy world, but that’s set outside the window here. The immersive sim on voyeurism. The immersive sim on watching your kid grow up. There’s like 100 different things you could imagine. There’s much, much more that can be done with this, other than: ‘I’m trapped in this environment and I’m running out of food and bullets, and monsters are coming in for me’. Now, that’s a fascinating game anyway – I don’t care what anyone says – I will always love that game. It’s just that funding those games would be incredibly difficult because they’re not all going to be breakout hits. It largely comes down to execution, audience tastes, and that sort of thing.”

The term ‘immersive sim’ is such a vague definition anyway. You have to be really plugged into the videogame industry to even know what it refers to, while something like ‘action game’ tells the audience exactly what they need to know: shit is getting blown up. Maybe we need to think of this approach to games more in terms of a design ethos, rather than trying to carve out a genre space for it – especially as its values bleed into other types of games. Maybe it is time for a change. Or maybe we start calling them first-person RPGs, or something similarly easy to communicate. Like a guy with dwindling supplies, trapped in a room as monsters claw at the wall, the genre might be forced to adapt, but it’s certainly not ready to crawl into the bin. In fact, Smith’s next game, Dishonored: Death of the Outsider, is out on September 15.