Hi. My name’s Jeremy, and I can’t stop unsheathing my weapon in public.

Listen: I can explain.

By pressing the tab key in Divinity: Original Sin 2, you command your character to pull out their blade and brandish it menacingly, allowing it to rest in their palm for a few seconds. That’s what I’ve been doing, about once every 30 minutes, since starting the game.

Related: the best RPGs on PC.

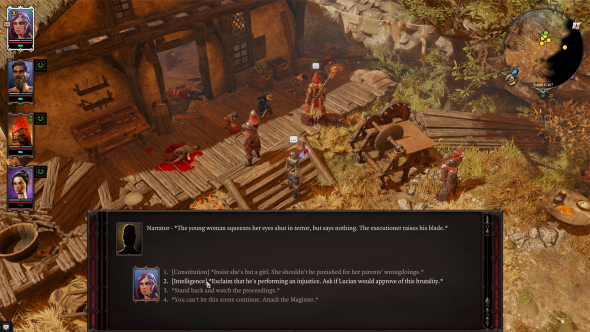

The practical applications of this little animation flourish are limited. It can make screenshots look more dynamic, if you’re so inclined. Or it can be used to test the limits of Larian’s simulation. Certainly, every time I take out my sword – usually in an inappropriate place, like a crowded camp or at the foot of a shrine to a dead god – the AI around me tend to react in horror, shouting warnings and ultimatums. Understandably. Who does that?

Well, me. But it’s an accident, your honour – a crime of muscle memory, if anything. The tab key means something else in Tyranny and Torment: Tides of Numenera, you see. In those games, it’s the button you press to see which objects around you can be rifled for treasure. And Divinity is intrinsically linked to Tyranny and Torment in some part of my brain beyond conscious reasoning.

That’s because, while Divinity: Original Sin launched into a world where the isometric RPG was newly revived, its sequel now forms part of a growing genre. It’s hard to view it apart from that context; hard not to notice where the series has begun to fall behind its peers, and where it strides boldly ahead.

In the solo (and, optionally, co-op) campaign that will be most players’ first port of call, the strengths are much the same as they were the first time around. Larian have wisely leaned on the elemental combat that powered Divinity: Original Sin – the same system that turned every battle into a bubbling broth of status effects. Fire arrows still ignite poison gas, rain spells extinguish flames, and electrical jolts turn steam into lightning clouds. The path to victory usually lies in catalysing an explosive reaction or three, and then making sure your opponents don’t get a chance to recover. It can be tough, since even the lowliest guard can take a fireball to the face and keep slugging. But finally felling your enemies, through wit and persistence, feels fantastic.

The genius lies in the way Larian’s meticulous simulation trickles out of the combat and into the game world at large. Where many turn-based RPGs tend to separate out roleplaying and conflict – church and state – in Divinity, one bleeds into the other. It’s not only that one character in your party can be having a chat while another flings fireballs in the next room. It’s that, when you wander past an open fire, the ‘warm’ effect is attributed to you for a few seconds. Or, if you cast the same teleportation spell that allows you to drop enemies into burning oil slicks, you might throw a companion over a ravine into an otherwise inaccessible area.

Combat is yours to start whenever and with whomever you see fit. And while traditionally that’s the sort of thing you did in RPGs only before a reload, Divinity can accommodate murder without consequence, so long as nobody’s within earshot or subsequently finds the body. Yep: NPCs have line-of-sight, which feeds into the game’s functional stealth system as well. Where triple-A RPGs tend to streamline towards the things you’re most likely to want to do – chat, kill, loot, repeat – Larian are committed to ensuring that all your sandbox whims are catered to.

One of Divinity: Original Sin 2’s most compelling new roleplaying options, however, comes straight from the triple-A space. RPGs there have found an awful lot of success in named protagonists – your Geralts and Shepards, defined to a degree but malleable enough to steer this way or that. And while Divinity: Original Sin 2 allows you to build a personality from the ground up, as you might have done in its predecessor, it now also lets you embody one of its companion characters instead.

This is, I’ve come to believe, the masterstroke of the campaign. I’ve been storming around the place as the Red Prince, a former lizard prince-general who’s been kicked out of his own empire for cavorting with demons. Basically Max Mosley with scales. Picking him immediately warps my dialogue options according to a number of factors, which the game flags up explicitly as ‘tags’ – the fact that I’m a huge, frightening lizard; my rarified attitudes as a noble; the particular yearnings of the Prince towards revenge and redemption. It’s rare that I’m not given the opportunity to be haughty or demanding in conversation – to lean into one side of the Prince’s personality or another, and find some personal investment within the framework I’ve chosen.

All of this gently encourages actual roleplaying, and is supported by an unusually robust relationship between quests and simulation. In your Divinity 2 playthrough, for instance, a former slave to the lizard empire named Sebille might be your protagonist, or a valued companion. In mine, she’s face down in an electrified puddle of her own blood. The campaign is sometimes astonishing in its ability to course-correct, and I’ve never run into a bug or disappointment when cutting a quest – or a life – short. But that’s not to say I haven’t encountered difficulties.

You should know that Divinity: Original Sin 2 will happily abandon a lovingly-written quest if you happen to snip one of its threads. On one level that’s admirable, and one of the key tenets of its sandbox. On another, it’s a bit frightening. At an early juncture I became stuck, only discovering through reference to a walkthrough that I’d unknowingly blocked two of three ways to progress – and entirely missed the third. I walked that last remaining questline very carefully indeed, as if it were a tightrope above a game-breaking abyss.

In similar fashion, combat can make progress teeth-grindingly tough. Play as one companion character, kill off another, perhaps rebuff a third for roleplaying reasons – suddenly you’re looking at an underpowered party in a campaign that can quickly get gruelling. The punishment is leavened to an extent in Explorer Mode, which buffs your friends and weakens your enemies, but only so far. It’s frustrating when Larian’s peers have established a new frictionless standard in this area – Story Time in Obsidian’s games, and Story Mode in Icewind Dale’s Enhanced Edition – that makes the genre truly accessible to those without the patience for micromanagement. Divinity 2 could stand to be that friendly.

Outside the campaign, though, Larian take the lead rather than lag behind. Competitive multiplayer could so easily have been an afterthought, but it turns out to be the best bit of the game – easily good enough to release as a standalone effort, if the studio had so desired.

Refitting the mechanics of a single-player campaign for satisfying online fisticuffs has proven too tricky a task for many RPG developers. Even the mighty Blizzard struggled for years to make Diablo III work as a competitive prospect. But, seemingly effortlessly, Divinity becomes a turn-based battler to match XCOM, Chaos Reborn, or the venerable Blood Bowl. Parties face off across arenas strewn with debris that make the most of the game’s systems – acid barrels, braziers, and fresh corpses stuffed with game-winning source magic.

In this new context, stealth and line-of-sight become primary concerns; ladders become choke points, loot chests the scene of backstab ambushes. In their intimacy and verticality, the maps are reminiscent of some of the smaller-scale Warhammer skirmish games – more Mordheim even than Mordheim: City of the Damned. In my experience, matches have been reliably tight and eventful, and often the perfect showcase for Divinity’s table-turning spell effects.

It’s my fervent hope that the elegant design on show here isn’t buried beneath discussion of the campaign, as XCOM’s multiplayer has been. It’s rare for a classic RPG to attempt full-fledged competitive adaptation. To do such a good job of it is frankly unheard of.

Perhaps bravest of all is Divinity 2’s Game Master mode – a powerful tool kit and asymmetrical multiplayer game that captures much of what tends to get left on the tabletop when D&D is synthesised for the PC. One player takes on the role of the Game Master, hosting a few others as they meander through an adventure – either one of Larian’s out-of-the-box modules, or a story they’ve conceived themselves.

Similar attempts have been made at this before. Neverwinter Nights, which Original Sin 2 so closely resembles in places, got halfway there in 2002. Sword Coast Legends gave it a shot only two years ago. But Larian’s Game Master mode outstrips its peers by dint of humility: it’s not overly attached to its own mechanics.

Sure, you’ve got that excellent combat engine to lean on if you fancy. But you could just as easily roll the dice to decide the outcome of an encounter – basing the maths on your favourite pen-and-paper ruleset, or simply making it up as you go. One of your adventurers with the Pet Pal talent wants to intimidate a dog? Sounds like a D20 job: let’s say they need an eight or higher to succeed, and away we go. The tale continues unabated.

Larian’s support for this kind of ad hoc adventuring extends to every aspect of the mode. If the highly specific or outlandish dialogue choice you’ve got in mind isn’t supported by the module you’re playing, well, the Game Master can simply type it into the box there and then.

The array of options might sound daunting, but here’s the important thing: you can take as much or as little of Divinity’s systemic framework as you want for your own adventures. In fact, I’m of the opinion that it’s at its best when you take very little, using what’s on-screen merely as visual reference and playing mainly in the shared imaginative space that tends to develop among any group having fun together.

Divinity: Original Sin 2 stands as a remarkable example of three genres: the classic roleplaying game, the online arena battler, and the tabletop-style adventure enabler. If its campaign fails to shake off some of Larian’s unfriendlier habits, those flaws are mitigated by the ways in which the studio have shaped a genre moulded by nostalgia into genuinely new forms – changing more than just the keyboard shortcuts for the better.